- Feb 4, 2026

Tuskegee Was Not an Isolated Event

- Eric Benjamin

- Chronic Disease Prevention, Health Equity & Medical History

- 0 comments

This post is part of a Black History Month series examining the medical history, biology, and systems that shape health outcomes for Black patients, from historical context to evidence-based prevention

When people hear about the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, it is often framed as a tragic outlier. A single unethical study. A mistake that medicine learned from and left behind.

That framing is incorrect.

Tuskegee was not an isolated failure. It was part of a pattern in American medicine, one in which Black patients were repeatedly studied, observed, and experimented on without consent, transparency, or the option to refuse.

Understanding that pattern matters, because it explains why mistrust did not come from nowhere, and why it has not simply faded with time.

What Actually Happened at Tuskegee

From 1932 to 1972, the U.S. Public Health Service enrolled Black men with syphilis in Macon County, Alabama. Participants were told they were receiving treatment for “bad blood.” In reality, many were never treated, even after penicillin became the standard of care in the 1940s.

Treatment was actively withheld.

Men were followed for decades as the disease progressed, resulting in preventable neurologic disease, cardiovascular complications, blindness, and death. Families were affected through congenital syphilis and loss of income and stability.

This was not ignorance. It was intentional non-treatment.

The shameful legacy of Tuskegee syphilis study still impacts African-American men today

Why Calling It an “Exception” Is Dangerous

Labeling Tuskegee as a singular event allows medicine to distance itself from responsibility. It implies the problem was a few unethical individuals rather than a system that permitted and protected unethical behavior.

But Tuskegee occurred in an era when:

Informed consent was routinely ignored for marginalized populations

Black patients were excluded from many hospitals while simultaneously used for research

Ethical standards were applied selectively

Tuskegee ended only after public exposure, not because the system corrected itself internally.

Other Documented Examples

Henrietta Lacks (1920–1951), whose cells became the first immortal human cell line used in biomedical research. Henrietta Lacks, oil on linen by Nelson Kadir

Tuskegee fits into a broader historical context that includes:

-

Non-consensual surgical experimentation on enslaved Black individuals

-

Radiation experiments conducted on Black patients without full disclosure

-

The use of Henrietta Lacks’ cells without her knowledge or consent, creating the HeLa cell line that transformed modern biomedical research

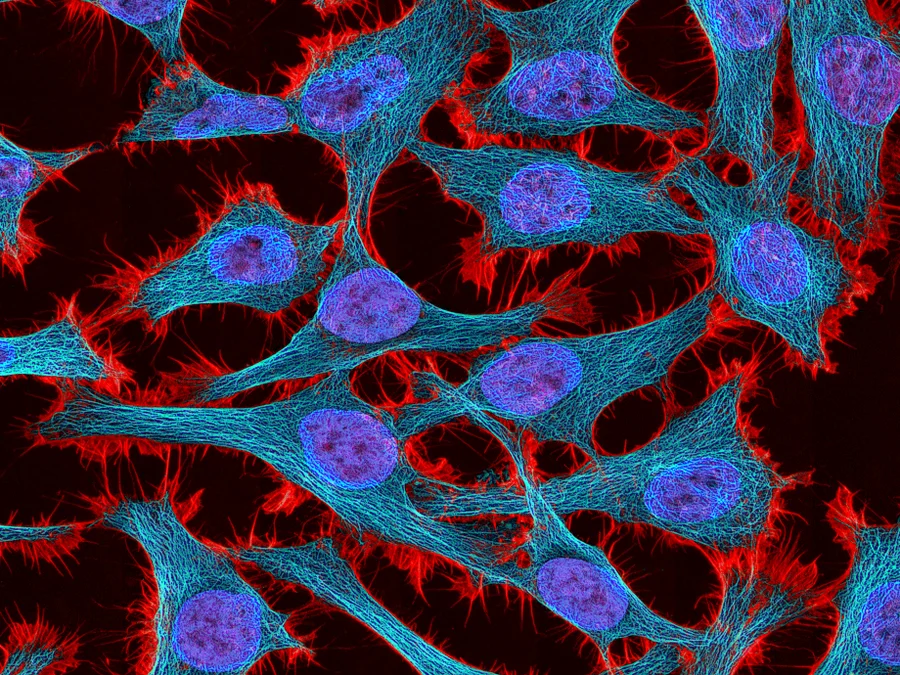

Multiphoton fluorescence image of stained HeLa cells. NIH Getty Images

These events were not hidden from the medical community at the time. They were normalized.

Why This History Still Matters in Exam Rooms Today

Medical mistrust is often framed as a cultural issue or a communication problem. The evidence suggests it is better understood as a learned response to repeated harm.

Studies consistently show that mistrust is associated with:

Lower screening rates

Delayed presentation for care

Reduced participation in clinical trials

Lower adherence to long-term treatment plans

When patients hesitate, question recommendations, or seek second opinions, this behavior is often mislabeled as noncompliance rather than recognized as contextual caution.

Ethical Reforms Came Late, and Trust Takes Time

Institutional Review Boards, informed consent standards, and research ethics regulations largely emerged after public outrage, not before harm occurred.

Even today, Black patients remain underrepresented in clinical trials, raising concerns about how well evidence applies across populations. Trust is not rebuilt by policies alone. It is rebuilt through consistent, transparent, respectful care over time.

What Clinicians Can Do Differently

Acknowledging this history does not weaken medicine. It strengthens it.

Clinicians can:

Be explicit about risks, benefits, and uncertainty

Encourage questions rather than rushing decisions

Avoid dismissing skepticism as ignorance

Recognize that trust is earned, not assumed

Good medicine is not just technically correct. It is ethically sound and relationally aware.

What Patients Can Do, Especially in Marginalized Communities

Patients should never have to compensate for failures in medical systems. Still, there are practical strategies that can help patients protect their health and advocate for themselves, particularly in environments where bias or dismissal may occur.

These are not solutions to structural problems, but they can improve real-world outcomes.

1. Ask for Clarity and Documentation

It is reasonable to ask:

“What are we ruling out?”

“What would make you change this plan?”

“Can this be documented in my chart?”

Clear documentation creates continuity and accountability, especially when care spans multiple clinicians.

2. Bring a Second Set of Ears When Possible

For important visits, having a trusted person present can:

Help retain information

Reinforce concerns if symptoms are minimized

Provide support during emotionally charged discussions

This is particularly helpful during complex diagnoses or treatment decisions.

3. Know That Questions Are Not Disrespect

Asking about risks, alternatives, or timelines is not being difficult. It is active participation in care.

Good clinicians welcome questions. If questions are discouraged or dismissed, that is a signal worth paying attention to.

4. Seek Second Opinions Without Guilt

Second opinions are a normal part of high-quality medical care. They are especially appropriate when:

Symptoms persist without explanation

A diagnosis does not fit the lived experience

Treatment plans feel rushed or incomplete

Seeking another perspective is not disloyal. It is protective.

5. Trust Patterns, Not Just Single Encounters

One difficult visit can happen to anyone. Repeated dismissal, rushed care, or lack of explanation is different.

If a pattern emerges, it is reasonable to seek care elsewhere when possible. Continuity matters, but so does feeling heard.

6. Remember That Hesitation Is Not Noncompliance

Caution, skepticism, and requests for more information are often responses to past experiences, not a lack of interest in health.

Patients deserve care that acknowledges context, history, and lived experience, not care that assumes resistance or disinterest.

A Shared Responsibility

Better medicine is not built by patients alone or clinicians alone. It requires systems that listen, clinicians who reflect, and patients who are supported rather than blamed.

Trust grows slowly, through consistent actions over time. Recognizing that reality is not a weakness in medicine. It is a necessary step toward improving it.Looking Forward

Tuskegee should not be remembered as a closed chapter. It should be remembered as a warning about what happens when power goes unchecked and voices are ignored.

This history does not define modern medicine, but it shapes how medicine is received.

Ignoring that reality does not move care forward. Facing it honestly does.

Eric Benjamin, PA-C

Preventive & Metabolic Health

Eat well. Move often. Age boldly.